There is a lot going on. Crash predictions abound, inflation fear is widespread, and confidence is thin, whether in markets or the wider economy. I want to draw together some of these threads we have covered in recent months, and add a bit more meat.

I have talked about The Age Of Fragility, and it has many strands – some are obvious, many others are more subtle or not yet visible. This is the nature of a highly complex system, the complex adaptive system which was explored in

Complex World, Simple Rules.

These are some of the more obvious fragilities:

Climate change – flood – drought – fires – pandemic – debt mountains – ageing populations – forced migration – inequality – US stock market bubble – investor mania, particularly younger people – cyber wars – China/US conflict – shortages – food poverty – fuel rationing – rising inflation – internet dependency – central bank errors.

Most of these cross-currents will persist for years to come, and it is foolish to pretend they do not exist.

Political Risk Is Trump Squared

Political risk sits across a number of these factors. Most politicians rightly want to “green the world” – it is a very urgent issue. But this will be expensive. Where will the money come from when there is already a debt mountain sitting atop the world?

These political considerations include some very practical issues. Who will tell the British and French farmers to tell the cows to stop eating grass? Who will tell less wealthy Europeans to get rid of the much-loved but “dirty” 15-year-old Fiat? And who will pay for the sparkly new e-car at over 40,000 euro?

The scope for ever more populist politicians to take advantage of this situation is very high, accompanied by civil unrest as the world, literally, burns. Trump may just have been the early mover – and there is a decent chance that he will be back too in 3 years.

The Awaited Policy Error

Nonetheless, there is a significant risk that they will amplify the errors to date with more of the same. In particular, it is notable that commodity shocks have caused recessions in the past, as central banks panic and raise interest rates. (As Ambrose Evan-Pritchard notes in the Telegraph, it is ironic that a young professor Bernanke wrote the definitive paper on this, and subsequently headed up the Federal Reserve and persisted with the Greenspan era errors)

This isn’t really about inflation (whether derived from a commodity shock or otherwise). It is about how central banks respond to inflation, and how, in turn, markets respond to central bank action.

The central banks have been on the hook, and procrastinated, for years on the matter of raising interest rates.

On the one hand, rising inflation can now act as the useful idiot for them to raise interest rates.

On the other hand, the risk to markets when they do raise rates is considerable, precisely because they haven’t raised rates earlier.

Interest rates have been kept at emergency levels long after the fire went out (roughly a decade ago), and has encouraged directors lining their pockets financial engineering, widened the wealth gap, and pushed the US stock market and global bonds to levels which are extremely dangerous, not just for investors, but for the stability of economies in general. The mountains of dodgy debt, built on central bank inaction, are ripe for collapse yet the debt/bond markets are needed to pay for greening the world, unless the bond markets are overhauled – but that’s another story.

The Siren Call Of The Averages

The market goes up 8-10% a year, on average. The market always recovers, in your limited experience as an investor. The central banks will always support the stock market – see above.

“The averages” hide an ugliness which the investment industry would rather you did not understand.

Part of the problem for investors is a deep misunderstanding of, or disinterest in, how markets really work by many of those on whom they tend to rely. This applies across fund managers and fund groups, advisers, the media, academia, regulators, and a motley collection who pop up everywhere with a strident view – typically inexperienced, unqualified, and unregulated. Of course, there are exceptions – but they are just that, exceptions.

If you think I am being harsh, look again at our findings. 94% of funds cannot beat an undemanding benchmark with any consistency. And these are the ones who are at least prepared to invest in a way which means they can be publicly monitored – many more do not e.g. discretionary investment services.

In recent days I have seen another of those “

The market crash is coming” articles, accompanied by a table headlined “

how long it took for the FTSE 100 to recover from crashes”. I have a number of issues with this, but it is the table which deeply worries me, and feeds the widespread belief that “markets always recover”. Most investors are totally unprepared for the risks, and do not understand the precedents. We have covered this many times, such as

The Dangerous Myth.

The Ugly Bear

Bears are not cuddly. They are deadly. They move fast. And they can stick around longer than you can stay solvent.

In the September teleconference, I used a number of slides to illustrate for how long a bear market can persist. This is important if you are at a certain stage in your life when a severe bear market will really hurt your quality of life, and create extreme stress which you would rather avoid.

John Hussman has added some colour to our previous analysis, with some help from Greg Jensen of Bridgewater.

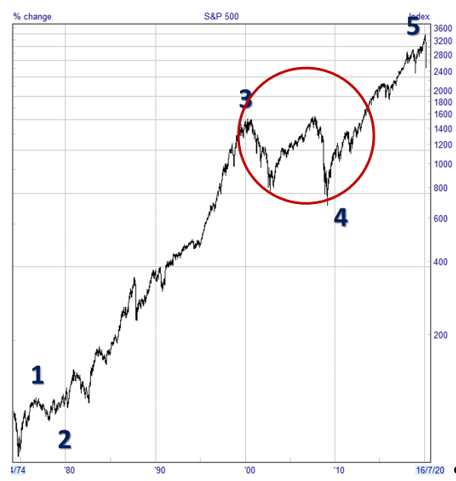

The four most prominent peaks in US market valuations, prior to the recent bubble, were 1905, 1929, 1965, and 2000. All such peaks are eventually broken, in one of two ways.

1929 and 2000 were resolved by crashes, with prices plunging by 50% or more.

The 1905 and 1965 extremes were instead resolved by some years of inflation, though they still encountered crashes midst those bear journeys.

For example, the Dow Industrials plunged by 49% from January 1906 to November 1907, then ground sideways for years. By December 1914, the market was still down by nearly half from its 1905 levels.

Likewise, although the initial market decline from the 1965 peak was a relatively modest 21%, the US market ground sideways until 1982, including an interim loss of nearly 50% during the very ugly 1972-74 bear market.

“It took 25 years for the market to reach again the high level of 1929…

…Dow Jones sold at the same high point in 1919 as it did in 1942 – 23 years later.”

Benjamin Graham, 1959

If this feels like the dim and distant, how about this interesting trip to nowhere from the US stock market which lasted 10 years, which was largely mirrored by the UK:

Coming Full Circle

Since 1987 markets have become accustomed to central banks bailing them out, and the scale of that largesse has grown with every crisis.

Central banks should have raised interest rates long ago. The idea is that interest rates should be raised when the going is good, otherwise there is little scope to cut rates in the next crisis or recession.

Higher inflation might now force their hands to raise rates, and damn the market consequences. Or, in contrast, it might just give them the excuse they need to raise rates to more sensible levels, and damn the market consequences.

Adding to the range of possible outcomes, not all central banks will necessarily respond in tandem – they are each under different domestic political influences, despite their apparent independence.

Meantime, politicians need money, and lots of it, to green the world. From where will that come? There is already a global debt mountain holding back economies – more on that another week. And politicians on the fringe are twitching to take advantage.

The possibilities are endless. You and I don’t need to try and understand the ins and outs of every possibility – we can safely let others attempt to do that.

You and I just need to understand how extreme valuations in markets have unwound in the past, and use that knowledge to encourage vigilance with our own portfolios and build on the foundation of your investment plan.