Over the last week, it has been the tech-focussed NASDAQ that has outperformed all other major stock markets around the globe. It is up 2.4%, the tech pot still boiling. India was up 1.4%, led up by domestic investors with little care for global events.

Over the last week, it has been the tech-focussed NASDAQ that has outperformed all other major stock markets around the globe. It is up 2.4%, the tech pot still boiling. India was up 1.4%, led up by domestic investors with little care for global events.

Commodities continued moving, with gold and copper up in excess of 2%.

The Nikkei was down 0.8%, which at this stage appears to be nothing other than sensible profit-taking, prompted by concerns over the yen. The Nikkei is home to many large global exporters, and so a weaker yen, making Japanese manufactures cheaper, tends to push up the Nikkei index.

Which brings us to the higher-than-expected US inflation numbers this week. This implies that US rates will stay higher, the dollar will stay strong against a weak yen, and the weak yen will in turn allow the Nikkei to continue upwards… unless the Japanese central bank takes more decisive action to reverse the weak yen… but decisive action is not their forte. In the short term I’m on the fence.

The S&P 500 peaked on 28th March. Despite the very poor inflation numbers this week, and a Truss-like moment in US bond markets, the S&P has not (not yet) broken decisively lower.

Taking a longer view of the US, the issue of “US exceptionalism” has been covered in teleconferences and blogs passim, and two weeks ago Bloomberg’s Edward Harrison set out to provide a more scientific answer. He compared the US with the UK, which on the face of it might seem unfair, but the results were intriguing.

In the wake of 15 years of massive US stock market outperformance, you might think that there is something unique about the US, which will keep their pot boiling. Yet going back to 1900, economic growth is little different between the US and UK. Breaking down the three decades up to 2018 there is also little significant difference, which certainly surprised me.

It is the stock market growth which is strikingly different.

For example, from the 2009 low the FTSE 100 has more than doubled, whereas in sharp contrast the S&P 500 was up by a multiple of 8, exceptional indeed. But if you go back before 2009 and observe complete cycles (the up and the down) the exceptionalism is not all it seems…

...In a nutshell, during economic expansions and bull markets for equities, the US stock market does sharply better. This appears to arise because larger sums are borrowed and bet on that expansion, particularly when there is some new technology to excite entrepreneurs and investors alike. Not only is it easier to borrow money in US upturns, but they are culturally more inclined to take on risk, and manic and over-confident investors inflate the stock market to bubble levels.

But when recession hits, and dashes the hopes of the over-borrowed, there is a lot of downside. This is when the UK stock market closes the gap against the US. It appears that over whole cycles (the up and the down), there is not so much difference between the US and UK.

This latest upward leg in the US cycle (both stock market and economy) hasn’t just been inflated by consumer and corporate debt, but also massive borrowing by the Biden administration to pump money into the US economy ahead of the Presidential election this November.

Harrison is concerned about this borrowing binge. “Peak to trough losses in the S&P 500 in the last two bear markets that coincided with normal-length recessions were over 40%”. With somewhat greater debt on this occasion it creates much greater risk than normal of “an outsized downturn in asset prices”. We interpret this as greater than 50%, and perhaps towards 70%.

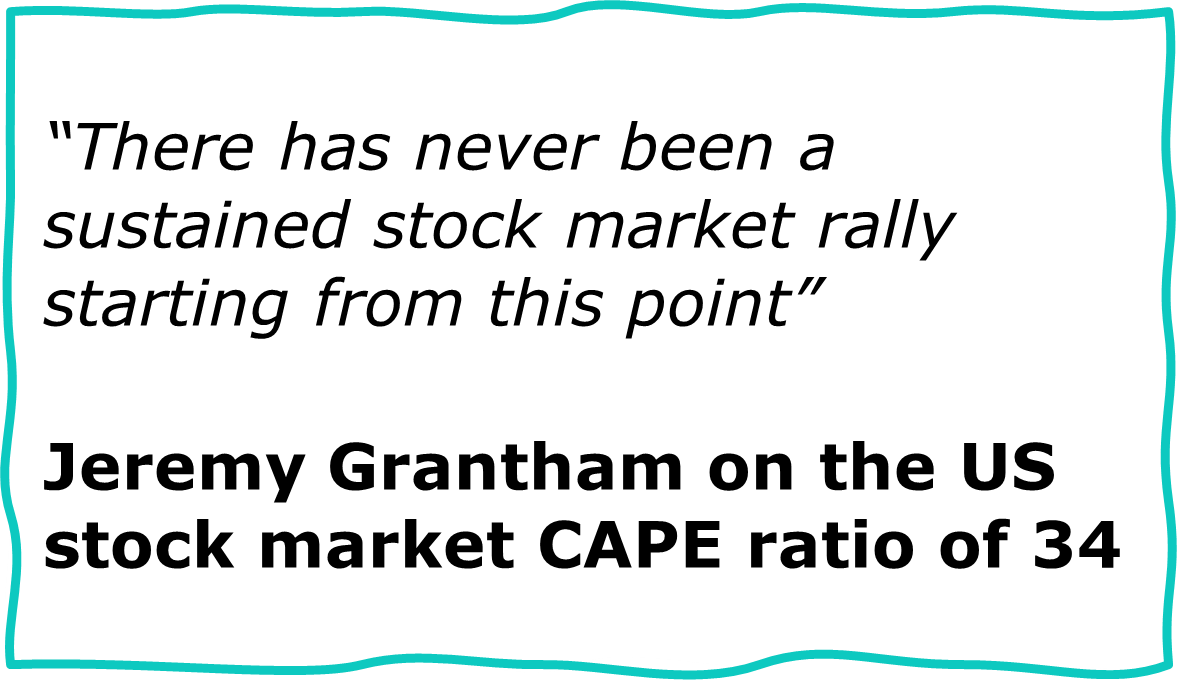

In a similar vein, Jeremy Grantham of GMO fame, coming at this solely from the angle of valuations, warns that “the long-run prospects for the broad U.S. stock market here look as poor as almost any other time in history”.

All of that being said, it leaves you in that very familiar and frustrating position of balancing opportunities where there is decent value (UK, Japan, commodities etc) against the considerable risks embedded in the US.