Should we be concerned about the investment implications of the latest coronavirus? Or is it just more media hype and hyper hysteria – last year Brexit, last week Meghan and Harry, this week a global plague???

It emerged on 31st December when the World Health Organization (WHO) was alerted by the Chinese authorities of a string of pneumonia-like cases in Wuhan, a city of 11 million people. The Chinese stock market was initially unconcerned and went up for a few more days.

As I write the Chinese stock market is still less than 3% lower than the level of 31st December. Similarly, the FTSE All-World index is down a nudge since the end of 2019 as well. So there hasn't been any dramatic swings in Chinese nor global markets as of yet. But we mustn’t be complacent, so below we look at precedents, wider implications, and what action you might take.

I should add, any illness that kills is horrific, and obviously worrying for those at risk. But this investment analysis is necessarily dispassionate.

What Happened In The Past?

Judging from the market moves during the onset of other infectious diseases, such as SARS in 2003, Ebola and avian flu, stock market investors should have little to fear.

The SARS outbreak occurred between November 2002 and July 2003 and infected more than 8,000, killing more than 770, a death rate of almost 10%. (As I write the current virus has 10,000 confirmed cases and 213 deaths, a mortality rate of under 2.15%)

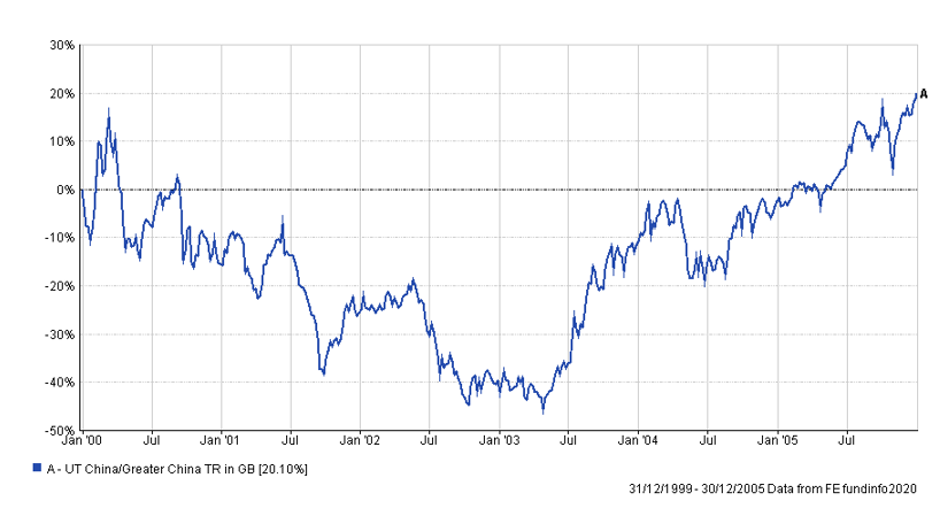

In chart 1 below you can see what happened in that period – nothing!

The SARS virus occurred when the Chinese stock market (represented here by the average fund in the China sector) had been trending down already for two years. In fact SARS coincided with a significant bottom for the Chinese stock market, it did not cause it.

Focussing in a bit more tightly, the MSCI Pacific ex Japan Index fell by 12.8% from 14 January to 13 March, as the news developed. However, markets subsequently rallied strongly and, for the year as a whole, the index went up 42.5%.

Chart 1

The point is that it is difficult to see any impact from prior outbreaks far more severe than that currently being encountered.

The most significant outbreak was the Spanish influenza pandemic of 1918, which is the catastrophe against which all modern pandemics are measured (and what we have now is not a pandemic, nowhere close). It is estimated that approximately 20 to 40 percent of the world population became ill, and that over 20 million people died. The US alone suffered approximately 500,000 deaths from flu between September 1918 and April 1919.

World War I was raging. The Dow Jones Industrial average fell about 30% from its highs while all these problems unfolded, but you cannot blame the flu epidemic – put another way, you have no way of knowing to what extent you should blame the flu epidemic.

Impact On China? And Other Assets?

On the face of it this outbreak could not come at a worse time for China’s economy, which slowed to a 6.1% rate of annual growth last year, the lowest reading in Beijing in nearly three decades.

Yet history suggests it should have no more than a temporary effect on economic growth (in China and globally), and that this will likely to be made up once the disease is brought under control.

Similarly, the impact on markets will be short-lived – some might see any weakness as a buying opportunity.

Commodities are typically volatile in any event. In 2003 oil was down nearly 20% at its trough during that epidemic, but the fear subsided when the pace of new cases slowed. The epidemic outbreak lasted about 5 months, before a quick economic, and oil price, recovery.

Most importantly, the coronavirus appears much less significant - less deadly and better contained.

The Three Big Changes Since 2003

The Chinese economy is vastly bigger than 2003, the government is more open, and much was learnt in 2003. Action taken so far in China seems sensible and textbook. That’s the good news.

The other two big changes are the internet and market vulnerability.

The growth of the internet, and the boom in social media are not helpful. Facebook didn’t start until 2004 and Twitter in 2006, and they now feed hysteria and panic in a way which didn’t occur in 2003. (Though, to be fair, they can also share very practical information, too.)

If the latter triggers nervous market reactions, these in turn can become self-fulfilling, partly because computers are programmed to sell on certain price falls, and because markets globally are inherently vulnerable due to considerable over-valuation in the pivotal US stock market and global bonds.

That market vulnerability is also greater than in 2003 because China is now so plugged in to the world economy.

How Should Investors Respond Now?

Unless this outbreak of coronavirus quickly becomes measurably more extreme than the SARS outbreak, market falls from this event should be short-lived.

Most importantly, such events should not be examined in isolation, but viewed in common with other prevailing market conditions. It is those other market conditions which have created the present vulnerability to a shock. This particular “shock” is probably not sufficient alone to drive markets down much lower, say 20-30%. But it does chip away at confidence, and confidence is what keeps the market afloat.

Unless you were specifically looking to buy into China a bit more cheaply (not in itself a terrible idea, which we explore here) you do not need to change your current investment strategy based on what we know about this virus, and recent precedents.

FURTHER READING